Introduction¶

Algorithmic trading refers to the use of computer programs to automate the process of making trading decisions and executing orders in financial markets. Although the term is widely used, its precise meaning can vary depending on the context and the regulatory framework. Two influential definitions are the following:

Bank for International Settlements (BIS, 2016)Markets Committee, Bank for International Settlements, 2016: Trading technology in which order and trade decisions are made electronically and autonomously.

MiFID II (Directive 2014/65/EU, Article 4, Definition 39)European Parliament and Council of the European Union, 2014: Trading in financial instruments where a computer algorithm automatically determines individual parameters of orders such as whether to initiate the order, the timing, price or quantity of the order or how to manage the order after its submission, with limited or no human intervention.

Notice that we use the terms algorithmic trading and automated trading as synonyms. In some references, algorithmic trading is used more narrowly to denote algorithmic execution, a specific form of automated trading focused on the optimal execution of predefined orders.

Algorithmic trading can be viewed as a subset of systematic trading, which refers to any trading strategy defined in a rule-based, methodical manner. It is also a subset of quantitative trading, where trading decisions follow the principles of the scientific method. In this framework, we first construct a scientific model of the trading environment—for example, a stochastic process such as a random walk—to represent market dynamics. This model is then used to derive inferences about quantities of interest, such as the likely range or direction of future prices. These inferences serve as inputs to mathematical optimization procedures, which determine the optimal trading actions—such as when and at what levels to trade—under given objectives and constraints.

The MiFID II definition is intentionally broad. It encompasses both complex, fully automated trading strategies and simpler automated rules, such as dynamic stop-loss orders or RfQ auto-negotiation rules. The exception being complex orders that are directly implemented within a exchange, which are considered part of the market infrastructure. In the following discussion, we will adopt the first, more restrictive definition, focusing on sophisticated algorithmic strategies where automation plays a central role in decision-making and execution.

High-Frequency Trading¶

High-Frequency Trading (HFT) is a subset of algorithmic trading distinguished by extremely short holding periods, rapid order submission and cancellation, and technological infrastructures designed to minimize latency. According to the Bank for International Settlements Markets Committee, Bank for International Settlements, 2016, HFT is a “subset of automated trading in which orders are submitted and trades executed at high speed, usually measured in microseconds, and a very tight intraday inventory position is maintained.” Such strategies seek to gain advantage from the ability to process information on market conditions and react almost instantaneously, typically resulting in a very large number of small trades, held for short periods, and generating substantial message traffic. To achieve this, HFT firms tend to place their trading servers physically close to the electronic market’s matching engines—a practice known as co-location—to minimize transmission delays or latency.

At the European regulatory level, MiFID II (Directive 2014/65/EU, Article 4(1)(40)) European Parliament and Council of the European Union, 2014 defines HFT as an algorithmic trading technique that relies on infrastructure designed to minimize latency, such as co-location, proximity hosting, or high-speed direct electronic access, and in which individual trades or orders are initiated, generated, routed, or executed by systems without human intervention. It also specifies that such activity typically involves high intraday message rates consisting of orders, quotes, or cancellations.

In practice, low-latency infrastructures are at the core of HFT. Co-location refers to hosting trading servers directly within or adjacent to an exchange’s data center to reduce round-trip latency to microseconds. Examples include Equinix LD4 in Slough (London) and NY4 in Secaucus (New Jersey), which host a large portion of global financial trading infrastructure. Proximity hosting involves maintaining servers in nearby facilities linked via dedicated fiber, while high-speed network access often relies on optimized fiber or microwave connections between major trading hubs (for instance, London–Frankfurt or New York–Chicago routes). Even marginal reductions in latency—on the order of microseconds—can yield significant competitive advantages in markets where prices evolve continuously and across fragmented venues.

HFT strategies themselves vary in scope and complexity. Common approaches include electronic market making, where firms continuously quote bid and ask prices and manage risk within very short horizons; statistical and cross-venue arbitrage, which exploit fleeting price discrepancies between related instruments or exchanges; latency arbitrage, which reacts faster than competitors to public information or order book events; and smart order routing, which optimizes execution quality across multiple venues, sometimes also to capture fee rebates or queue priority. These strategies generate immense volumes of order messages and depend critically on precise market data, optimized software, and sophisticated risk controls.

From a regulatory perspective, MiFID II and MiFIR introduced a harmonized framework for algorithmic and high-frequency trading, elaborated through Regulatory Technical Standard 6 (RTS-6) European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), 2016, which defines organizational, risk-control, and testing requirements. As with all European directives, MiFID II provisions must be transposed into national law, and implementation may differ across jurisdictions. For example, Germany’s High-Frequency Trading Act Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (BaFin), 2013 introduced an explicit authorization regime for HFT firms and added an additional criterion based on the speed of the connection, ensuring that firms not genuinely engaged in high-frequency activity would not fall under the same regulatory burden. These frameworks impose significant obligations on HFT firms, including mandatory system testing, kill switches, message-rate controls, record-keeping, and stringent resilience standards—all of which contribute to higher compliance costs and operational complexity.

Despite their efficiency benefits, HFT firms have attracted public and regulatory scrutiny. Critics argue that practices such as latency arbitrage or preferential access to dark pools create an uneven playing field, eroding confidence in market fairness. Michael Lewis’s Flash Boys Lewis, 2014 popularized this perception by portraying HFT as exploiting microscopic speed advantages to anticipate and “front-run” slower participants, contributing to the view that HFT is inherently predatory. Although many of these practices are fully compliant with market rules, they raise ethical and transparency questions, particularly in fragmented markets where access to speed and information is uneven.

Regulators are also concerned about the systemic implications of HFT. The Flash Crash of May 6, 2010 U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission and U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, 2010 illustrated how rapid, automated interactions among algorithms could amplify volatility and cause temporary dislocations. Two main risks are frequently cited European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), 2019 Bank for International Settlements (BIS), 2018: false liquidity—where HFT appears to provide deep liquidity in normal conditions but withdraws it abruptly during stress—and algorithmic herding, when many algorithms respond similarly to the same signals, creating self-reinforcing price dynamics. To mitigate these risks, regulators have implemented safeguards such as circuit breakers, message-rate limits, and system testing obligations.

Yet, it is important to balance these concerns against the structural role HFT plays in modern markets. By continuously arbitraging prices across venues, narrowing spreads, and enhancing price consistency, HFT contributes to market efficiency and liquidity provision under most conditions. The regulatory challenge is therefore not to constrain speed itself, but to ensure that technological advantages do not compromise fairness or stability. In this sense, HFT embodies both the promise and the tension of modern market microstructure: the pursuit of efficiency through automation, bounded by the need to maintain integrity and resilience in the face of ever-faster financial systems.

Algorithmic Trading Growth¶

The growth of algorithmic trading is closely tied to the broader electronification of financial markets, since of course algorithms can only in principle operate when markets provide electronic protocols for submitting, routing, and cancelling orders automatically. Traditionally, this requirement limited algorithmic participation to venues with fully electronic limit-order books or standardized API-based access. However, this constraint may gradually weaken with the emergence of Generative AI models—large language models, multimodal systems, and real-time audio models—that could enable algorithmic strategies to interact with voice, chat, and email-based trading workflows. Such systems may eventually allow automation to extend into execution channels that historically relied on human-to-human communication, potentially reshaping parts of OTC, RFQ, and relationship-driven markets.

Across major markets, empirical studies consistently show a structural transition from manual and voice-based execution to electronic and then algorithmic execution. SEC market-structure analyses report that by the late 2010s much of U.S. trading activity in the capital markets is executed electronically, with automated execution constituting a large portion of activity U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, 2020. Measurements of algorithmic and HFT share vary depending on methodology—whether based on order messages, trade count, or value traded—but most empirical work places algorithmic/HFT participation in U.S. equities in the range of 40–60% during the 2010s. Studies using more recent data at millisecond or microsecond granularity reveal that while HFT’s share of displayed liquidity peaked in the mid-2010s, algorithmic activity remains central to U.S. market functioning. A recent reconstruction of HFT participation from 2012 to 2023 shows persistent, high algorithmic involvement across the full universe of listed stocks Boehmer & others, 2024

In Europe, ESMA’s empirical reviews of MiFID markets confirm that algorithmic trading expanded rapidly after 2007, driven by fragmentation and the introduction of new trading venues. While HFT participation in European equities is generally found to be lower than in the United States —often around one-third of trading depending on the metric—, algorithmic order submission and cancellation rates are substantial, and similar structural patterns emerge: high electronic venue reliance, dense order-book activity, and widespread use of automated execution by intermediaries and buy-side institutions European Securities,Markets Authority, 2014 European Securities,Markets Authority, 2021. ESMA’s multi-year datasets also document significant cross-country heterogeneity, with markets such as the UK and the Netherlands exhibiting higher algorithmic intensity than smaller or less-fragmented continental venues.

In the Asia–Pacific region, algorithmic trading expanded at a later stage but has shown strong growth wherever electronic limit order-book infrastructure is well developed. Empirical studies on the Tokyo Stock Exchange report substantial algorithmic and HFT participation from the mid-2010s onward, driven by improvements in exchange matching technology Hosaka, 2014. Similar patterns appear in Australia, Korea, and, increasingly, select Chinese markets. The region is more heterogeneous than Europe or the United States: in several Asian jurisdictions the persistence of voice or hybrid OTC mechanisms constrains the penetration of high-speed algorithmic strategies. Where low-latency access and co-location are available, algorithmic trading tends to scale rapidly.

The growth of algorithmic trading also differs markedly across asset classes. Equities exhibit the deepest empirical record: numerous studies show that algorithmic execution and HFT reshaped equity microstructure by increasing order-book depth, tightening spreads, and raising message traffic. Futures and derivatives markets have experienced a similarly strong expansion. CFTC-backed studies show that between 2012 and 2018 many major U.S. futures contracts saw sharp increases in HFT share, in some cases more than doubling relative to early-2010s baselines Haynes & Roberts, 2022. Derivatives markets, being fully electronic and centrally cleared, are particularly conducive to high-speed algorithmic strategies, and empirical work documents widespread cross-asset and cross-venue arbitrage activity.

FX markets present a more complex case due to their predominantly OTC structure. BIS fact-finding studies nonetheless show rising algorithmic and HFT presence in electronic spot-FX platforms such as EBS and Reuters venues Bank for International Settlements, 2011. Here, algorithmic trading is concentrated in highly liquid currency pairs (G10 countries) and in segments where anonymous, central-limit-order-book trading is available; elsewhere, voice trading and relationship-based bilateral execution remain dominant.

In fixed income markets the evidence points to a steady but uneven rise in automation. ICMA and New York Fed research finds that electronification, especially on all-to-all corporate bond platforms and electronic interdealer Treasury markets, has enabled algorithmic strategies to scale. However, voice and RFQ mechanisms continue to retain significant market share in many bond categories. Algorithmic market making in bond futures has grown particularly quickly, mirroring the pattern observed in equity index futures Bech et al., 2016 Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 2015.

Finally, cryptocurrency markets have undergone one of the fastest transitions to algorithmic execution. Empirical studies using millisecond-level data show that, from the mid-2010s onward, many large crypto exchanges experienced rapid growth in latency-sensitive strategies, cross-venue arbitrage, and automated market making. Fragmentation across exchanges, low latency APIs, and continuous trading environments have resulted in market microstructures that resemble early electronic equities: high message traffic, narrow spreads in liquid pairs, and a strong role for algorithmic intermediaries Makarov & Schoar, 2020.

Taken together, empirical research shows that algorithmic trading expands most rapidly in markets that have electronic order books, provide direct or low-latency access, and standardize market data and clearing processes. Regional patterns differ: U.S. markets lead, Europe follows with strong regulatory oversight, and Asia expands heterogeneously, but the underlying trajectory is similar. Across asset classes, algorithmic activity is most advanced in equities and futures, growing in FX and fixed income as electronification proceeds, and already dominant in many crypto venues. The result is a global, multi-asset shift in which algorithmic strategies have become a central mechanism for price formation, liquidity provision, and execution quality in modern markets.

Reasons to use Algorithmic Trading¶

The widespread adoption of algorithmic trading across financial markets is driven by a combination of technological, economic, and organisational factors. At its core, algorithmic trading enables market participants to operate more efficiently, consistently, and at scale than would be possible through purely manual processes.

A primary motivation for using trading algorithms is speed. Computer algorithms can submit orders and react to changes in market conditions in timeframes far shorter than those accessible to human traders. In electronic markets, where prices and liquidity can change within milliseconds, this speed advantage is often essential, particularly for strategies that rely on short-lived opportunities or rapid risk adjustments.

Closely related to speed is the ability of algorithms to perform large-scale information processing. Trading algorithms can simultaneously monitor and analyse multiple data sources, including prices, order books, volumes, and derived indicators across many instruments and markets. This parallel processing capability allows algorithms to detect patterns and respond to market signals that would be difficult or impossible for a human trader to observe in real time.

Algorithmic trading also provides scalability. Once developed, an algorithm can be deployed across a large number of instruments, markets, or client orders with minimal incremental cost. This enables firms to increase trading activity and market coverage without a proportional increase in human headcount. Scalability is particularly important for institutions managing large portfolios, operating multiple strategies concurrently, or providing execution and liquidity services to many clients.

Another key advantage is the promotion of systematic trading. Algorithms enforce a disciplined and repeatable decision-making process, reducing the influence of emotions such as fear, overconfidence, or hesitation. This systematic approach facilitates rigorous evaluation of strategy performance using historical data, allows meaningful comparisons between alternative strategies, and supports continuous improvement through testing and refinement. While systematic trading is not exclusive to algorithms, automation makes it far easier to apply consistently over time and at scale.

Trading algorithms are also naturally aligned with a quantitative approach to trading, so much than in Bank for International Settlements, 2011, they are defined as “the use of computers and advanced mathematical models to make decisions about the timing, price and quantity of a market order”. They enable the explicit formulation of objectives—such as minimising execution costs, controlling inventory risk, or maximising profit and loss—within a mathematical or statistical framework. By doing so, algorithms can optimise trading decisions in a consistent manner, subject to clearly defined constraints. This is particularly evident in execution algorithms that seek to minimise transaction costs and in market-making algorithms that aim to balance profitability against inventory and risk limits.

Finally, algorithmic trading helps to reduce human errors. Manual trading is susceptible to operational mistakes, such as incorrect order sizes, prices, or instruments, often referred to as “fat-finger” errors. By automating order generation and routing, algorithms can significantly lower the incidence of such errors. At the same time, it is important to recognise that automation introduces its own set of risks, including software bugs, model errors, and system failures. These risks do not negate the benefits of algorithmic trading, but they do require robust governance, testing, and monitoring frameworks, which are addressed in later chapters.

A Brief History of Algorithmic Trading¶

The evolution of algorithmic trading is deeply intertwined with the broader digitisation of financial markets. In the 1970s and 1980s, exchanges began computerising order workflows, while quantitative finance—particularly the Black–Scholes framework Black & Scholes, 1973—rapidly entered trading practice. Black–Scholes provided a replicating-portfolio logic that could be encoded into dynamic rules, enabling strategies such as portfolio insurance, which sought to mimic a put option by mechanically selling futures as markets fell. As computers automated these adjustments, model-driven execution became one of the first large-scale uses of electronic trading logic. During the 1987 crash, the procyclical behaviour of these strategies—selling as prices declined—was widely seen as amplifying market stress, revealing how model-based, computerised trading could interact with volatility in destabilising ways.

Through the 1990s, electronic trading accelerated. Several U.S. exchanges migrated to fully electronic execution, and new electronic communication networks (ECNs) such as Island and Archipelago fostered a more competitive, fragmented market structure. Decimalisation in 2001 further reduced tick sizes and compressed spreads, creating conditions that favoured automation. Early statistical arbitrage strategies, including pairs trading, became prominent in this era, with pioneering work at Morgan Stanley and subsequent developments by David Shaw, James Simons, and others who would later build systematic hedge funds. At the academic frontier, Bertsimas and Lo Bertsimas & Lo, 1998, followed by Almgren and Chriss Almgren & Chriss, 2000, created a rigorous mathematical foundation for optimal trade execution, establishing the framework that still underpins institutional execution algorithms today.

The 2000s saw rapid advances in connectivity, co-location, and message-handling infrastructure. As latency budgets shrank, high-frequency trading (HFT) grew from a niche practice into a major component of equity-market activity. Regulatory changes—in particular Regulation NMS in the United States and MiFID I in Europe—encouraged venue competition and liquidity fragmentation, making automated smart order routing essential for best execution. Around the same period, Avellaneda and Stoikov (2008) Avellaneda & Stoikov, 2008 introduced a dynamic framework for limit-order-book market making, which became one of the theoretical cornerstones of modern electronic liquidity provision.

By the end of the decade, HFT accounted for a substantial share of U.S. equity volumes, though competition subsequently reduced margins. The “Flash Crash” of 6 May 2010 demonstrated the speed and interconnectedness of automated strategies: a large sell algorithm interacting with aggressive HFT flows produced a rapid, self-reinforcing price collapse across multiple asset classes before markets recovered minutes later. After 2010, firms increasingly pushed for technological edge through specialised hardware such as FPGAs and—critically—through the deployment of microwave and later millimetre-wave transmission networks. These reduced Chicago–New Jersey latency close to the physical limit achievable in the atmosphere.

During the 2010s, automated ingestion of unstructured data emerged as another frontier. Firms began deploying real-time news analytics, and by 2012 platforms such as Dataminr enabled machine-readable detection of market-relevant events from public information flows. Twitter-based signals were incorporated into professional terminals, although early episodes such as the 2013 hacked Associated Press tweet showed the risks inherent in embedding fast-reaction systems into the market ecosystem. Meanwhile, crypto-asset markets developed their own microstructures, with HFT-style market making and arbitrage quickly dominating trading on major exchanges by the mid-2010s.

The late 2010s brought an increase in experimentation with machine learning in execution optimisation, short-horizon prediction, and market-making parameterisation. Reinforcement learning, in particular, attracted academic and industry attention, although deployment into truly latency-critical or autonomous production systems remained limited. Most firms adopted ML in peripheral or advisory capacities—signal generation, short-term prediction, and parameter tuning—rather than placing machine learning models directly “in the loop” for continuous order submission.

The 2020s introduced several structural developments. Cloud-based trading infrastructure matured, allowing firms to shift large-scale analytics, simulation, and historical data processing to scalable cloud compute while continuing to run their latency-sensitive components on dedicated hardware. Alternative datasets, spanning geospatial indicators, mobility traces, supply-chain data, and ESG-linked information, became integrated into quantitative research pipelines, further blurring the boundary between traditional quant signals and broader data science.

Generative AI technologies, including large language models, began to influence research, monitoring, and operational workflows. Firms are actively experimenting with these tools—for example in news classification, documentation analysis, surveillance, and compliance—but there is little evidence of LLMs being embedded directly into production trading engines. Their role remains largely complementary: accelerating research, aiding supervision, or supporting decision-making rather than autonomously driving order flow.

Events such as the extreme volatility during the COVID-19 market shock reinforced the centrality of algorithmic trading to market functioning: automated execution models proved adaptable under stress, yet liquidity provision by HFT market makers contracted at critical moments, widening spreads and exposing structural fragilities. In crypto-asset markets, the 2022 crisis offered a parallel demonstration of algorithmic microstructure dynamics—latency races, liquidity evaporation, and execution-layer vulnerabilities—within a largely unregulated environment.

Across these decades, algorithmic trading evolved from a narrow automation tool into a comprehensive technological discipline encompassing market microstructure, optimisation, data engineering, and increasingly advanced machine learning. While the foundational principles of execution and liquidity provision remain rooted in the early models of the 1990s and 2000s, the field continues to expand, shaped by hardware frontiers, data availability, and new analytical methods. The next stage of development will likely come from integrating these elements—systematic modelling, high-performance infrastructure, and advanced AI—while maintaining the stringent reliability and control standards required in live markets.

Types of Trading Algorithms¶

Trading algorithms can be grouped into a small number of broad categories according to their primary economic objective and their mode of interaction with financial markets. While real-world strategies often combine elements of more than one category, this classification provides a useful analytical framework for understanding the role algorithms play in modern trading systems. At a high level, trading algorithms can be divided into execution algorithms, market-making algorithms, and investment algorithms. Each category reflects a distinct function within the trading process, ranging from the efficient implementation of decisions, to the provision of liquidity, to the allocation of capital with the expectation of future returns.

Execution Algorithms¶

The goal of executing algorithms is to buy or sell a financial instrument minimising the transaction costs. In this setting, the decision to trade is taken outside the algorithm, for example by a portfolio manager, risk manager, or also another trading algorithm. The algorithm’s role is to determine how to trade, taking into account market conditions, liquidity, and the structure of the trading venue.

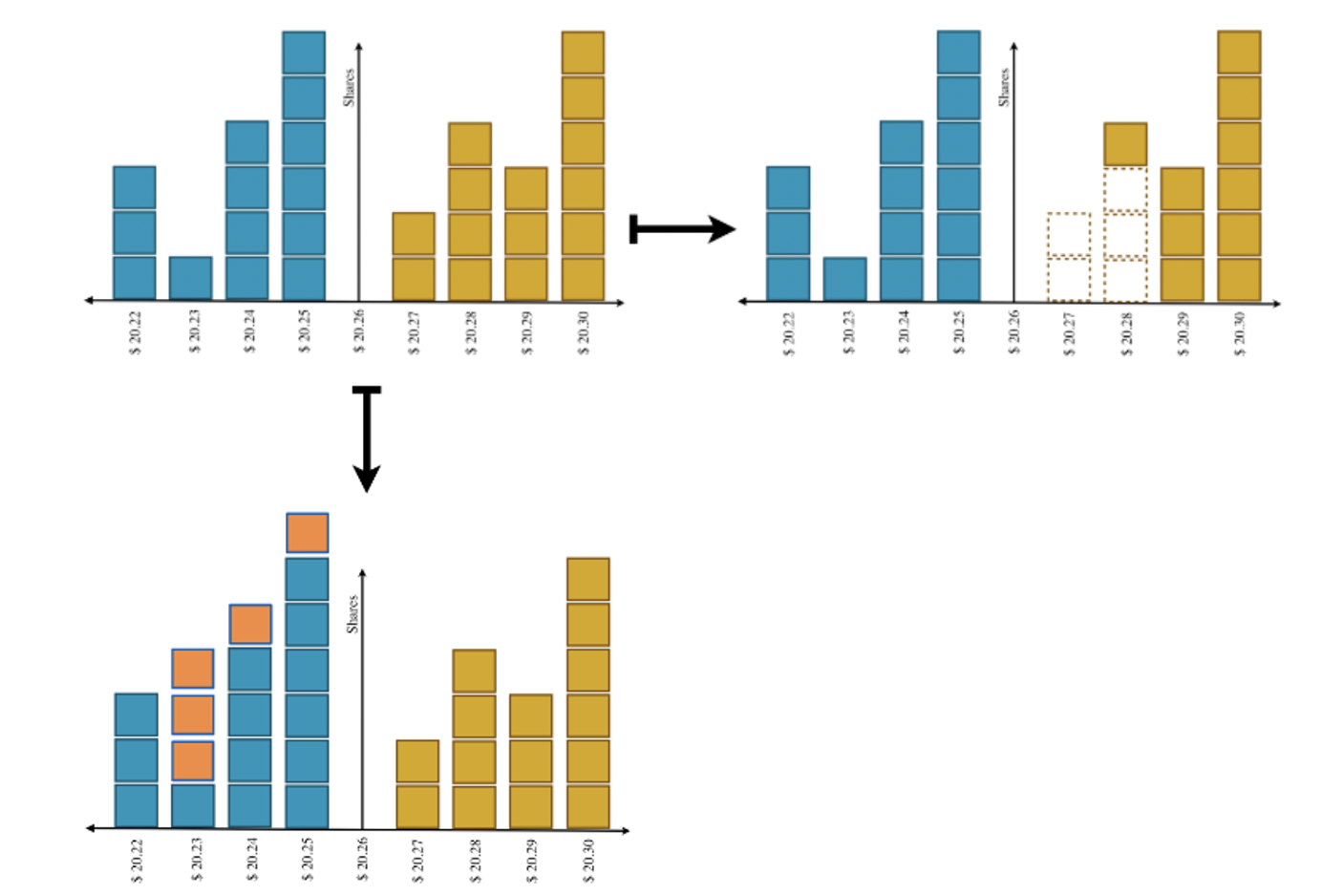

These algorithms are particularly important when trading large volumes in markets organised around a limit order book. Liquidity at the best bid or offer is often insufficient to absorb a large order without significant price concessions. A naïve execution, such as submitting a single market order, would therefore result in substantial transaction costs, also called temporary market impact. The alternative of using limit orders does not guarantee execution and might signal other players the interest to transact. They might react modifying their orders in a way that adversely impact our cost of execution, for example by removing orders in the opposite side of the order book and placing them at less favourable prices. In both cases, the information conferred by these orders might produce a longer term effect on the other players, for instance affecting the likelihood of arrival of other investor’s orders or the price at which they are willing to trade. This is called the permanent market impact. The following figure illustrates this trade-off at the level of primitive orders.

Figure 1:Illustration of the trade-off between executing an order in a limit order book (upper left) using market orders (upper right) or limit orders (lower left). Market orders guarantee immediacy of execution but incur in worse execution prices, since they consume the available liquidity. Limit orders can execute at more favourably prices, but their execution is not guaranteed.

This trade-off between market impact and execution probability is at the heart of the design of execution algorithms. Notice that execution probability translates into market or price risk if the algorithm must fill the full order, since prices might move adversely (but also, of course, favourably) if the order is not executed immediately. In general, execution algorithms seek to address this problem by intelligently deciding how to split the full order (also called the parent order) into smaller chunks (child orders) in order to reduce the market impact while keeping price risk under control. The algorithm not only decides the type and size of the child orders. It also can delay their submission to avoid leaking information to the market and expecting that the liquidity consumed will be replenished by new orders arriving to the market.

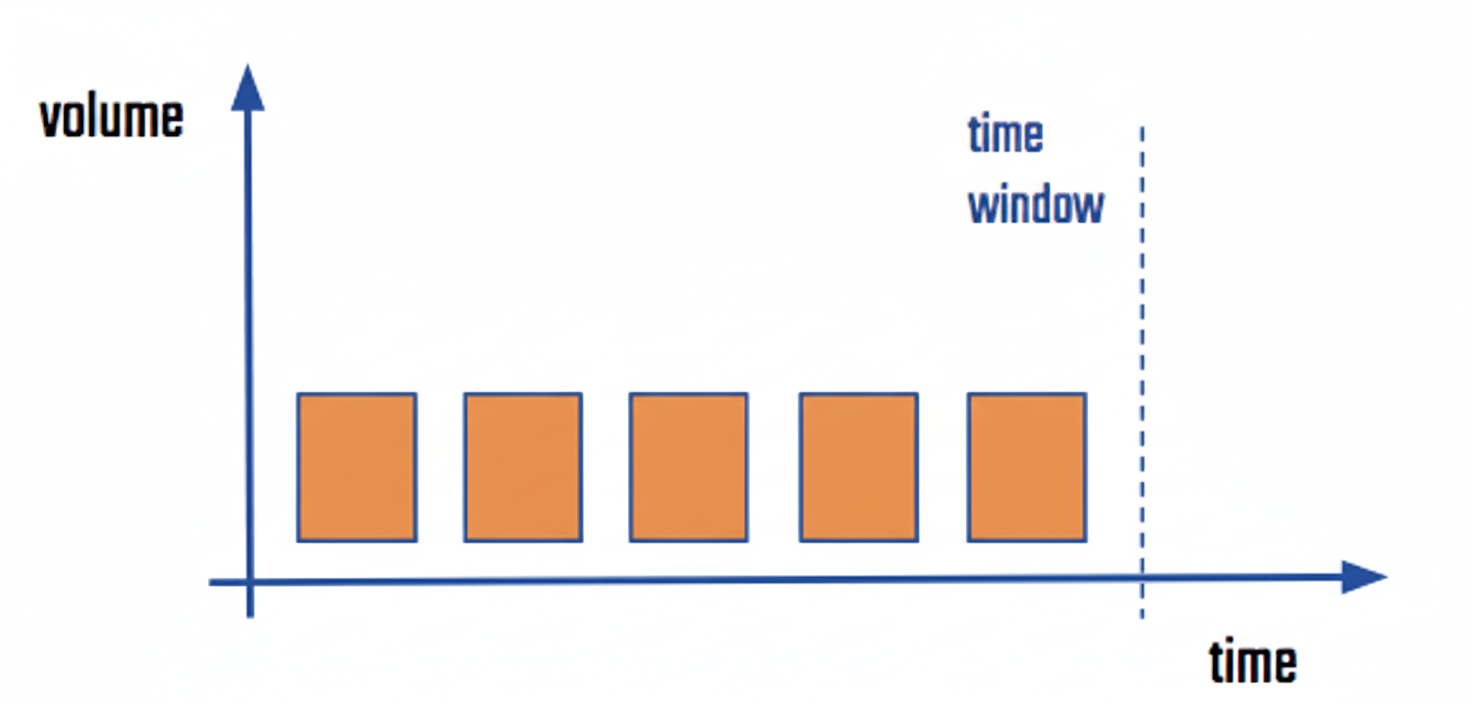

For example, a simple execution strategy is the TWAP (Time Weighted Average Price), which splits the order in chunks of equal size that are executed over a given period of time (e.g. a trading session) during certain allocated time buckets (e.g. five minutes buckets). For example, an order of 300 shares to be executed during the next hour using a TWAP algorithm could be divided in twelve chunks of 25 shares to be executed every 5 minutes. Every chunk of 25 shares is then executed in the limit order book using primitive orders, e.g. a combination of limit orders and market orders. The following figure illustrates such strategy.

Figure 2:Simple sketch of Time Weighted Average Price (TWAP) execution schedule, where an equal number of shares are allocated to equal time buckets over the proposed execution period. Within each bucket, the allocated order is executed using a combination of primitive orders. A TWAP strategy is a simple way to reduce market impact in execution without compromising the execution of the full order.

As we wil discuss in chapter Execution fundamentals, there is a large variety of standard execution algorithms that can be used depending on the objectives and profile of the party submitting the order. For instance, for orders that target the average price of the orders executed in the market during the execution window, there is the VWAP (Volume Weighted Average Price) algorithm. And the family of Implementation Shortfall execution algorithms allow to adjust the market impact vs price risk trade-off to the risk tolerance of the investor.

Market-Making algorithms¶

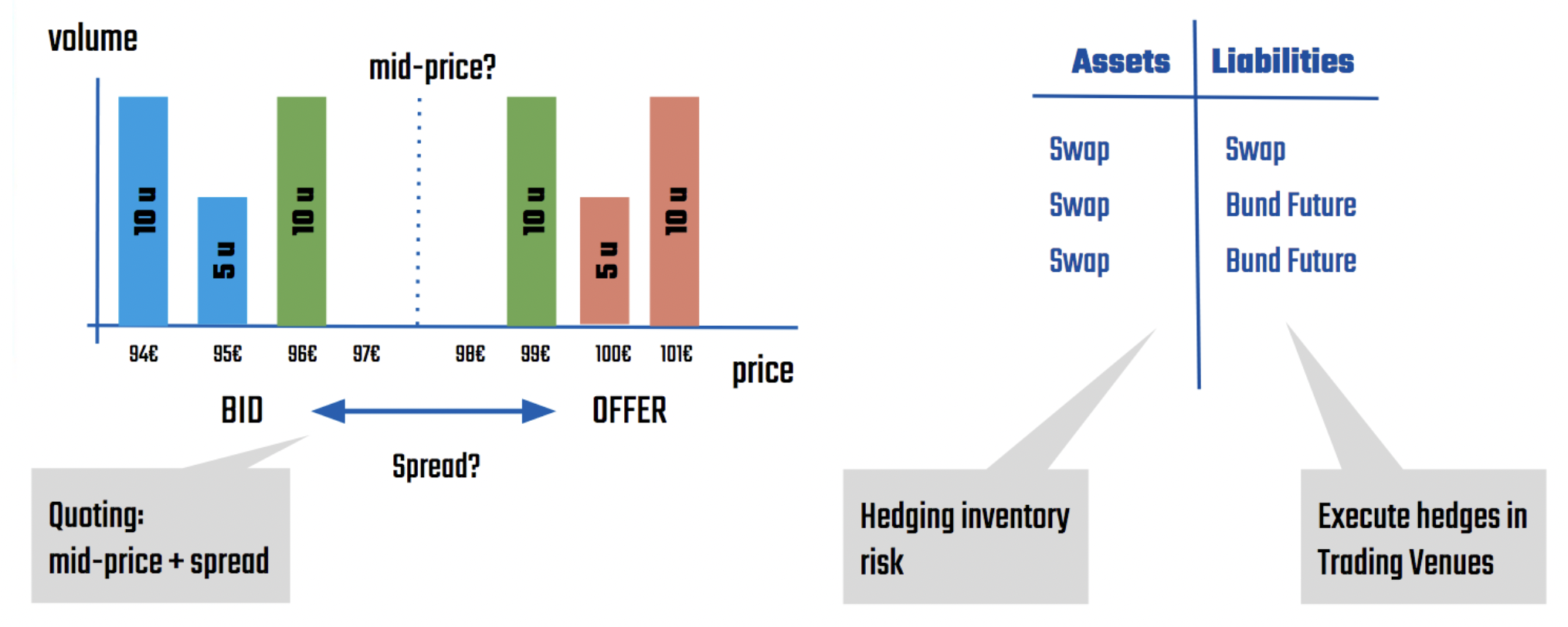

Market-making algorithms are concerned with the continuous provision of liquidity to financial markets. These algorithms stand ready to buy and sell a financial instrument by continuously quoting bid and ask prices. The economic compensation for providing this immediacy is the bid–ask spread, which must cover both operating costs and the risks inherent in the activity.

Two main sources of risk characterise market making. The first is inventory risk, which arises because the market maker must hold positions in order to provide liquidity. If prices move unfavourably, the value of this inventory may decline. The second is information asymmetry, whereby counterparties may trade on superior information, leaving the market maker exposed to adverse selection. These risks explain why market makers typically quote prices away from a perceived fair value rather than at the mid-price. Additionally, the market-maker needs to strike a balance between the frequency of trading and the profitability per round-trip of buying and selling, determined by the spreads quoted. Since a high-frequency and low-profit strategy can be seen to have a lower volatility of overall profits & losses for the market-maker, this trade-off is also considered a form of risk, named transactional risk.

Algorithmic market making automates the process of quote generation and risk management. A full market-making algorithm typically needs to maintain good estimations of the fair price of the instrument quoted and determine appropriate bid and ask quotes around that price, taking into account current market conditions and internal risk constraints. Quotes may be adjusted asymmetrically to manage inventory, for example by quoting more aggressively on one side of the market to reduce accumulated exposure. In many implementations, inventory risk is further mitigated through automatic hedging using correlated instruments. The following figure sketches the components of a market-making algorithm for Interest Rate Swaps:

Figure 3:A market-making algorithm for standard Interest Rate Swaps (IRS) quoted in interbank markets based on a limit order book. The main components of the algorithm are 1) fair price determination (mid-price in the order book), 2) spread determination, 3) hedging portfolio exposures, in this case using liquid futures on government bonds.

These algorithms are widely used by broker-dealers, particularly for smaller transactions, allowing human traders to focus on larger or more complex trades. They are also central to the business models of electronic liquidity providers and high-frequency trading firms. Market-making algorithms operate across different market structures, including order-driven, quote-driven, and hybrid markets, adapting their logic to the specific rules and microstructure of each venue.

Investment algorithms¶

Investment can be widely defined as the allocation of scarce resources with the expectation of future benefits. In particular, investment strategies in the financial markets allocate such resources to financial instruments, after a careful analysis of future profit opportunities. Investment trading algorithms simply execute these strategies autonomously using computers. Given the generality of this objective, it is not surprising that investment algorithms encompass a large variety of different strategies. And although it is possible to categorize broadly these strategies in families that share a common pattern for the source of profits, in practice investors that implement investment algorithms spend a fair amount of time trying to find new types of strategies or unexplored asset classes or markets where existing strategies can be applied. The reason is that as soon as certain investment strategies become popular, those trades become crowded and profit opportunities fade away quickly.

Investment algorithms can operate over different time horizons, and the role of automation varies accordingly. A useful distinction can be made between intraday investment algorithms and investment algorithms operating over longer horizons.

Intraday investment algorithms focus on short-term opportunities that may persist for minutes, seconds, or even fractions of a second. These strategies aim to exploit transient patterns in prices, order flow, or relative valuations, such as short-term momentum, mean reversion, or arbitrage opportunities across instruments or venues. In this context, algorithms are often essential rather than optional: the speed at which signals emerge and decay makes manual trading impractical. As a result, intraday investment algorithms are typically implemented in a fully automated manner and are closely linked to market microstructure, execution quality, and latency.

By contrast, investment algorithms operating over longer time horizons —such as days, weeks, or months— often play a more varied role. In some cases, algorithms are used primarily as decision-support tools, systematically analysing data and generating signals that inform human investment decisions. Orders may then be executed manually or via standard execution algorithms. This hybrid approach is common in traditional asset management, where explainability, governance, and oversight considerations may limit full automation.

In other cases, particularly in systematic and robo-investment strategies, algorithms take on a more comprehensive role. They may determine asset allocation, rebalance portfolios periodically, and manage risk in a largely automated fashion. Execution itself may still be delegated to specialised execution algorithms, but the investment logic —how capital is allocated across assets and over time— is embedded directly in the algorithmic framework.

As the number of strategies, instruments, or portfolios managed by an institution increases, the economic rationale for automation becomes stronger. Managing a large and diverse set of investment strategies manually is costly and error-prone, even when trading frequencies are relatively low. In such environments, investment algorithms provide scalability, consistency, and the ability to manage complexity in a controlled and systematic way.

Developing Trading Algorithms¶

Developing a trading algorithm is a structured and iterative process that begins with a clear definition of its objectives. The purpose of the algorithm dictates the approach, data requirements, and performance metrics. For execution algorithms, the primary objective is to minimize transaction costs and market impact when buying or selling large volumes of assets. This often involves breaking down orders into smaller trades and executing them over time or across multiple venues to avoid moving the market. For market-making algorithms, the goal is to provide liquidity by continuously quoting bid and ask prices, profiting from the spread while carefully managing inventory risk and adverse selection. Meanwhile, intraday investment algorithms aim to generate returns by exploiting short-term price inefficiencies, arbitrage opportunities, or momentum effects, where speed and precision are critical.

Once the objective is defined, the next step is to establish how the algorithm’s performance will be measured. The choice of benchmarks is crucial, as it determines how success is evaluated and how different strategies are compared. Performance metrics vary depending on the type of algorithm. For example, execution algorithms are often evaluated based on their ability to achieve a favorable average price relative to the market, while investment strategies focus on risk-adjusted returns and drawdowns. Market - making algorithms typically track the profit & loss of the portfolio, as well as specific liquidity provision measures like the percentage of time during the market hours that bid and ask quotes were posted (for LOB based market-making) or the percentage of request for quotes for which a price has been provided (for RfQ based market-making).

Data plays a central role in algorithmic trading. The type and quality of data required depend on the strategy: high-frequency trading demands ultra-low-latency, tick-level data, while longer-term strategies may rely on daily or hourly price series. Historical data is used for both backtesting and calibrating the algorithm’s parameters. However, it is essential to recognize the limitations of historical data, as markets evolve and past performance does not guarantee future results. Overfitting—where an algorithm is excessively tailored to historical patterns—can lead to poor performance in live trading. To address this, developers use techniques such as out-of-sample testing, cross-validation, and stress testing under different market conditions.

The design phase is where the algorithm is developed. There are several approaches to strategy creation:

Mathematical Optimization: Techniques like Dynamic Programming or Mean - Variance optimization are used to design a strategy that achieves the selected goal.

Machine Learning: Algorithms can be trained to recognize patterns in market data, adapt to changing conditions, or predict short-term price movements. In addition, techniques like Reinforcement Learning can be used for developing adaptive trading strategies.

Heuristic Rules: Some strategies are based on empirical observations or trader intuition, codified into rules that guide the algorithm’s actions. While these may lack the complexity of data-driven models, they can be effective in markets where human judgment is still valuable.

Hybrid Approaches: Many algorithms combine elements of the above, leveraging machine learning for pattern recognition and mathematical optimization for efficient execution.

After the design phase, the algorithm is implemented in code, typically using languages such as Python, C++, or Java, depending on performance requirements. The algorithm is then tested in a controlled environment, first through historical backtesting and later in real-time simulations or paper trading. Backtesting helps assess how the algorithm would have performed in past market conditions, but it is important to account for transaction costs, slippage, and market impact, which are often overlooked in simplified tests. Stress testing under extreme scenarios—such as flash crashes or periods of low liquidity—helps identify potential vulnerabilities before deployment.

Deployment marks the beginning of a new phase: continuous monitoring and refinement. Markets are dynamic, and an algorithm that performs well in one regime may struggle in another. Real-time analytics are used to track performance and risk metrics, allowing for quick adjustments if needed. Successful algorithmic trading requires not only robust initial development but also ongoing adaptation to maintain effectiveness in changing market conditions.

Benchmarks for Algorithmic Strategies¶

The choice of benchmarks depends on the type of algorithm and its objectives. Below are the most common benchmarks used in the industry, defined mathematically where applicable:

Execution Strategies¶

For algorithms focused on executing trades with minimal market impact, the following benchmarks are typically used:

Close: The mid-price of the asset at the time the strategy completes execution.

Market Order Close: The cost of executing a market order at the end of the strategy’s time horizon, using the notional value of the strategy.

Open-High-Low-Close (OHLC) Average: The average of the mid-prices at the open, high, low, and close during the execution period.

Time Weighted Average Price (TWAP): The arithmetic mean of the asset’s price over the execution window, calculated as:

where is the mid-price at time and is the number of time intervals.

Volume Weighted Average Price (VWAP): The average price weighted by trading volume over the execution period, calculated as:

where is the price at time and (V_i) is the volume traded at that time.

Decision Open: The mid-price of the asset at the time the strategy is initiated.

Market Order Decision Open: The cost of executing a market order at the time the strategy is launched, using the notional value of the strategy.

Arrival Open: The mid-price of the asset when the first order generated by the strategy reaches the market.

Market Order Arrival Open: The cost of executing a market order at the time the first order reaches the market, using the notional value of the strategy.

Market-Making and investment Strategies¶

For algorithms designed to generate returns or provide liquidity, such as market-making, momentum, mean-reversion, or arbitrage strategies, the following benchmarks are commonly used:

Profit and Loss (P&L): The cumulative return of the strategy over a given period, starting from an initial position or inventory.

Sharpe Ratio: Measures the excess return per unit of risk (volatility), defined as:

where is the expected excess return of the strategy over a risk-free rate, and is the standard deviation of the strategy’s returns.

Beta (): Indicates the sensitivity of the strategy’s returns to market movements. A beta greater than 1 suggests the strategy is more volatile than the market, while a beta less than 1 indicates lower volatility.

Maximum Drawdown: The largest peak-to-trough decline in the strategy’s cumulative returns over a specified period. It is a measure of downside risk.

Sortino Ratio: A variation of the Sharpe ratio that focuses on downside volatility, defined as:

where is the average return, is the target return (often the risk-free rate), and is the standard deviation of negative returns (downside deviation).

Omega Ratio (): Compares the probability of achieving returns above a threshold to the probability of returns below that threshold, defined as:

where is the cumulative distribution function of returns, and is the target return.

Market-making algorithms are also evaluated based on their ability to provide liquidity consistently and effectively. The following metrics are commonly used:

Percentage of Time Quoted (LOB-based market making): The proportion of the trading session during which the algorithm maintains active bid and ask quotes in the limit order book (LOB). This reflects the algorithm’s presence and commitment to providing liquidity.

Percentage of Requests for Quote (RfQs) Quoted (RfQ-based market making): The ratio of RfQs for which the algorithm returns a price to the client, calculated as:

Hit Ratio (RfQ-based market making): The ratio of RfQs that result in a trade (hit) to the total number of RfQs received, defined as:

Hit & Miss Ratio (RfQ-based market making): The ratio of RfQs that result in a trade (hit) to the total number of RfQs that are closed by any dealer (i.e., the client traded). This excludes price discovery RfQs where the client did not trade, and is calculated as:

Algorithmic Trading Infrastructure¶

The effectiveness of an algorithmic trading strategy is not solely determined by the sophistication of the algorithm itself, but also by the robustness and efficiency of the infrastructure that supports it. A well-designed infrastructure ensures low latency, high capacity, and resilience—qualities that are indispensable in modern electronic markets. The infrastructure required for algorithmic trading is composed of several interconnected components, each playing a critical role in the execution, monitoring, and optimization of trading strategies.

Core Requirements¶

To support the demands of algorithmic trading, the infrastructure must meet several fundamental requirements:

High speed and low latency: delays in transmitting data or executing orders can significantly impact performance, particularly for high-frequency trading (HFT) strategies, where microsecond-level latency can make the difference between profit and loss. The necessary latency threshold depends on the type of algorithm and the markets in which it operates. For instance, HFT strategies often require microsecond-level precision, while execution algorithms may tolerate slightly higher delays.

Capacity: algorithmic trading generates a vast number of messages due to the high frequency of orders, cancellations, and updates. The infrastructure must be capable of handling this volume without degradation in performance, ensuring that the system remains responsive even during periods of peak activity.

Resiliency: the system must include mechanisms for monitoring performance in real-time and handling failures gracefully. This includes the ability to disconnect from the market quickly and orderly if necessary, as well as redundant systems to ensure continuity in the event of hardware or software failures. Resiliency also involves implementing pre-trade and post-trade controls to prevent errors and detect potential market abuse, ensuring that the trading process remains both efficient and compliant.

Key Components of Algorithmic Trading Infrastructure¶

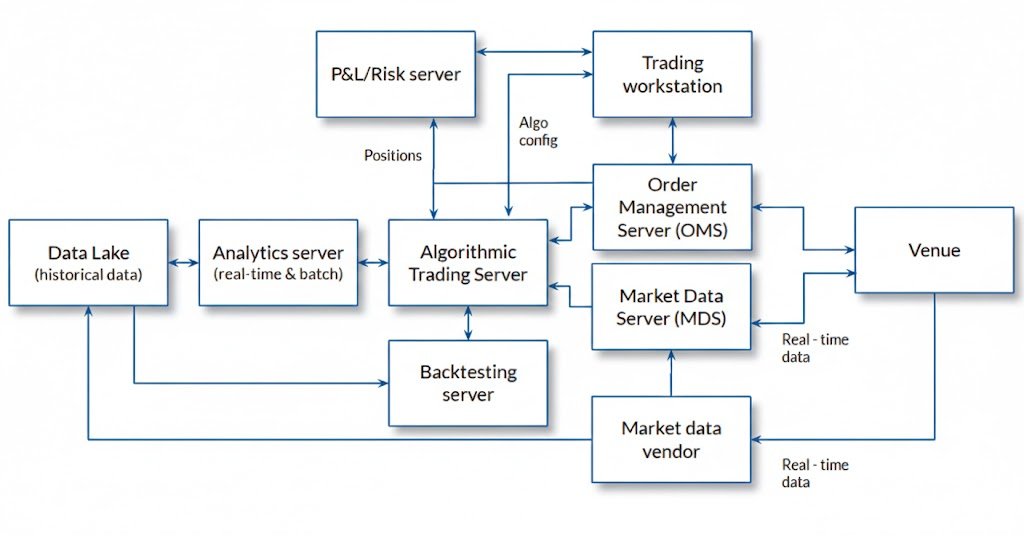

A robust algorithmic trading system relies on modular, interconnected components, each designed for a distinct role in the trading workflow. While real-world setups may consolidate some functions—especially in smaller or simpler systems—the architecture naturally evolves toward this specialized structure as complexity and scale increase. Below, we break down the key elements of this framework, as illustrated in the following figure.

Figure 4:Architecture of an algorithmic trading system. The overall principle for the template is based on encapsulation and functional specialization of each component.

Algorithmic Trading Server¶

The algorithmic trading server, often referred to as a “strategy container,” is the core platform where trading algorithms are executed. It generates orders based on the algorithm’s logic and reacts to real-time market data. There are several approaches to building this component, each with its own advantages and trade-offs.

Firms may choose to use third-party servers that include a suite of pre-built algorithms. These platforms often provide tools for developing proprietary strategies, ranging from support for traditional programming languages to complex graphical interfaces. Examples of such providers are Algo Trader, Pragma360 and QuantConnect.

On the other hand, large brokers, dealers, and hedge funds often develop their own algorithmic trading servers in-house. This approach allows for greater customization and differentiation, as proprietary algorithms can be tailored to specific market conditions and trading objectives. The choice of programming language depends on performance requirements, with high-performance code typically written in languages like Java, C#, or C++, while Python and MATLAB are often used for prototyping and less latency-sensitive applications.

The server typically employs complex event processing (CEP) logic to handle real-time data streams and make rapid trading decisions. They are also sometimes built using reactive programming principles, which allow the system to respond dynamically to changes in market conditions, further enhancing the agility and responsiveness of the trading infrastructure.

Market Data Server (MDS)¶

The Market Data Server (MDS) serves as the central hub for both historical and real-time market data, which is essential for algorithm calibration, backtesting, and live trading. Historical data is stored in a “data store,” “data lake,” or “data repository” and is used for calibrating and backtesting strategies. KDB+ remains the industry standard for handling time-series data due to its in-memory performance and ability to process vast datasets at high speed. It is widely used in finance for algorithmic trading, risk management, and market surveillance, particularly in environments where latency and accuracy are paramount.

For real-time data, firms can obtain market data either directly from trading venues or through vendors like LSEG (acronym for London Stock Exchange Group, which bought Refinitiv, previously known as Thomson Reuters) or Bloomberg. While vendors offer the advantage of a single point of access and standardized data formats, connecting directly to exchanges can reduce latency, which is critical for high-frequency and latency-sensitive strategies. For professional applications, it is recommended to have at least two alternative data sources to ensure redundancy and reliability.

Order Management System (OMS)¶

The Order Management System (OMS) is responsible for handling all orders sent to trading venues. It manages order entry, routing, and status monitoring, as well as trade booking and reconciliation. Key functionalities include order entry, which can be done manually or via algorithms, and order routing, which involves encoding orders according to a standardized protocol and transmitting them to trading venues.

The Financial Information eXchange (FIX) protocol remains the most widely used standard in electronic trading, providing a consistent and efficient means of communication between clients, brokers, and exchanges. OMS platforms such as Bloomberg AIM, Fidessa OMS, and FIS Valdi continue to be prominent in the industry, offering robust solutions for managing order flow across multiple asset classes and regions.

Execution Management System (EMS)¶

While OMS platforms focus on order management, Execution Management Systems (EMS) are specialized for order execution and algorithmic trading. EMS platforms often overlap with OMS in functionality but are more outward-facing, offering connectivity to multiple exchanges, brokers, and trading platforms. They provide tools for pre-trade and post-trade analysis, real-time monitoring, and Direct Market Access (DMA).

Bloomberg EMSX remains a leading EMS platform, offering global, broker-neutral equities and futures trading, as well as integration with Bloomberg’s buy-side OMS, AIM. EMSX supports a wide range of asset classes, including equities, futures, options, and index swaps, and provides access to nearly every listed market through its extensive network of broker destinations.

Market Making Trading Platforms¶

For firms engaged in market-making activities, specialized platforms are available that provide tools for managing Request for Quote (RfQ) and Request for Stream (RfS) workflows. These platforms typically include pricing and quoting engines, auto-quoting and auto-hedging capabilities, and integration with OMS and EMS.

Itiviti, now part of Broadridge, continues to offer a suite of market-making solutions, including Tbricks and Orc Trader, which are designed for listed derivatives and provide real-time risk control and customization. Numerix Oneview for Trading offers real-time pricing, market data management, and risk calculations for structured products and derivatives. ION Trading is a major player offering platforms for Fixed Income trading.

Analytics and Backtesting Server¶

The analytics server is used for off-line analysis, including the calibration of algorithm parameters and performance evaluation. It relies on historical or synthetic data to simulate how strategies would have performed under different market conditions. Historical data reflects real market conditions but is limited to past scenarios, while synthetic data can be generated to simulate a wider range of market conditions, including extreme or unlikely scenarios.

Platforms like QuantConnect and Deltix provide comprehensive backtesting and analytics capabilities, allowing traders to test and refine their strategies before deployment.

Profit & Loss (P&L) and Risk Server¶

The P&L and risk server tracks the real-time performance of trading positions, providing metrics such as profit and loss, exposure, and risk indicators. These systems are often integrated with the firm’s broader risk management infrastructure but may include specialized features for algorithmic trading.

Murex MX.3 is a leading platform in this space, offering integrated solutions for trading, risk management, and processing across a wide range of asset classes. It provides real-time risk monitoring and analysis, enabling institutions to identify and mitigate potential risks promptly.

Infrastructure for Small Firms and Private Investors¶

Not all market participants require the same level of infrastructure. Small firms and private investors often rely on third-party solutions that bundle algorithmic trading servers, analytics, backtesting, and connectivity to brokers and exchanges.

Platforms like MetaTrader 5 (MT5), Interactive Brokers, and QuantConnect offer accessible and cost-effective alternatives, providing a range of tools for developing, testing, and deploying trading strategies. Crowdsourced hedge funds such as Numerai and Quantiacs continue to provide environments for developing and backtesting trading algorithms, with the best-performing strategies potentially being included in the fund’s portfolio.

For those with limited resources, open-source libraries like PyAlgoTrade, Zipline, and Backtrader provide cost-effective alternatives for backtesting and strategy development. Cloud infrastructure from providers like AWS, Google Cloud, and Microsoft Azure further enhances accessibility, allowing traders to scale their operations without significant upfront investment.

- Markets Committee, Bank for International Settlements. (2016). Electronic Trading in Fixed Income Markets [Markets Committee Papers No. 7]. Bank for International Settlements. https://www.bis.org/publ/mktc07.htm

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union. (2014). Directive 2014/65/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council on Markets in Financial Instruments (MiFID II). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%253A32014L0065

- European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA). (2016). Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2017/589 — Regulatory Technical Standards (RTS 6) specifying organisational requirements of investment firms engaged in algorithmic trading [Techreport]. European Securities. https://www.esma.europa.eu/document/technical-standards-mifid-ii-mifir

- Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (BaFin). (2013). German High-Frequency Trading Act (Hochfrequenzhandelsgesetz) [Techreport]. Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (BaFin). https://www.bafin.de/EN/Aufsicht/HandelMarkt/HighFrequencyTrading/highfrequencytrading_node_en.html

- Lewis, M. (2014). Flash Boys: A Wall Street Revolt. W. W. Norton & Company.

- U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission and U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. (2010). Findings Regarding the Market Events of May 6, 2010 [Techreport]. U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission. https://www.sec.gov/news/studies/2010/marketevents-report.pdf

- European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA). (2019). ESMA Report on High-Frequency Trading Activity in EU Equity Markets [Techreport]. European Securities. https://www.esma.europa.eu/document/esma-report-high-frequency-trading-activity-eu-equity-markets

- Bank for International Settlements (BIS). (2018). Monitoring of Fast-Paced Electronic Markets [Techreport]. Bank for International Settlements (BIS). https://www.bis.org/publ/mktc13.pdf

- U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. (2020). Staff Report on Algorithmic Trading in U.S. Capital Markets [Techreport]. U.S. Securities. https://www.sec.gov/files/algo_trading_report_2020.pdf

- Boehmer, E., & others. (2024). High-Frequency Trading in U.S. Equity Markets: A 2012–2023 Reconstruction. arXiv Preprint arXiv:2004.06627.

- HFT Activity in EU Equity Markets. (2014). [Techreport]. European Securities.

- High-Frequency Trading Activity in EU Equity Markets. (2021). [Techreport]. European Securities.

- Hosaka, G. (2014). Analysis of High-frequency Trading at Tokyo Stock Exchange. Shōken Anarisuto Jānaru, 52(6), 73–82.

- Haynes, R., & Roberts, J. S. (2022). Automated Trading in Futures Markets - Update #2 [Techreport]. Commodity Futures Trading Commission.

- Bank for International Settlements. (2011). High-frequency trading in the foreign exchange market [Techreport]. Markets Committee. https://www.bis.org/publ/mktc05.pdf